The Rise of Bahāʾu’llāh in Baghdad

In 1863, in the Iraqi city of Baghdad, an Iranian man named Mirza Husayn Ali Nuri declared that he was the final prophet sent by God and the promised Messiah, whose coming had been foretold in both Christianity and Islam. On this occasion, he adopted the title Bahāʾuʾllāh, meaning “the Glory of God”, while his followers came to be known as Bahāʾīs. Adherents of this religion claim that the Bahāʾī Faith is currently spreading rapidly across the world.

Part 1: Who Was the Bāb? Origins of Bābism and the Bahāʾī Faith in 19th Century Iran

In fact, the roots of the Bahāʾī Faith begin even before Bahāʾuʾllāh. In the early nineteenth century, Iran—considered a stronghold of Shiʿa Islam—was facing political and social instability. This was also a period when one thousand years had passed since the occultation of the Twelfth Imam, Imam Mahdi. As a result, some Shiʿa scholars and members of the public claimed that the return of the Hidden Imam was imminent.

Documentary: Who Are Bahāʾīs? What is Bahai Religion? From Imam Mahdi to the Bahāʾī Faith (Part 2) | Wisdom House

During this time, a twenty-four-year-old young man from Shiraz, Sayyid Ali Muhammad Shirazi, declared that he was the gateway (Bāb) to the Hidden Imam, and he became known as the Bāb. Later, the Bāb claimed that he himself was the Imam Mahdi and also proclaimed prophethood. Over time, he gained many followers, who came to be known as Bābīs. However, in 1850, the Qajar monarchy executed the Bāb by firing squad.

Succession After the Bāb: Ṣubḥ-i Azal and Bahāʾu’llāh

In 1850, when the founder of the Bābī religion, the thirty-year-old Sayyid Ali Muhammad Shirazi (the Bāb), was executed by the Qajar monarchy, the Bāb had, before his death, appointed his nineteen-year-old follower Mirza Yahya Nuri as the leader of the Bābī community. At the same time, the Bāb told his followers that the “Light of God” would soon appear among them. Mirza Yahya Nuri adopted the title Ṣubḥ-i Azal.

In 1852, members of the Bābī movement attempted to avenge the execution of their religious leader. They carried out an unsuccessful assassination attempt on the Qajar king in Tehran, during which the Shah was injured. In retaliation, the state launched large-scale reprisals against the Bābīs, killing many and arresting others, who were imprisoned.

To escape arrest and persecution, the new Bābī leader Ṣubḥ-i Azal was also forced to flee Iran. He migrated to the neighboring country of Iraq, settling in the city of Baghdad.

Meanwhile, large numbers of Bābīs were being arrested in Iran. Among those arrested was Mirza Husayn Ali Nuri, the brother of the new Bābī leader Ṣubḥ-i Azal. He belonged to the elite and one of the wealthiest families of Tehran and was born in 1817.

When the Bābī movement began in 1844, Mirza Husayn Ali Nuri became an important follower of the Bāb. In Tehran, he turned his own house into a center of the Bābī movement, where people were encouraged to join the new faith. He also had close social connections with senior government officials and foreign diplomats. The Bahāʾī scholar Moojan Momen, in his book The Bahāʾī Faith, writes that Mirza Husayn Ali Nuri’s sister was married to an official at the Russian embassy in Iran.

Because of these connections, when the Qajar government imprisoned him in 1852 for his links with the Bābīs, Russian influence played an important role in securing his release. He was freed on the condition that he would leave Iran and go to Russia. Under Russian pressure, the Iranian monarchy released him. However, instead of going to Russia, he went to Baghdad, where his brother Mirza Yahya Nuri (Ṣubḥ-i Azal), the Bābī successor, was living.

Ṣubḥ-i Azal and Bahāʾu’llāh: Split

In 1863, Mirza Husayn Ali Nuri claimed that he was the “manifestation of God” whose appearance had been foretold by the founder of the Bābī religion, the Bāb. In this way, he separated from his brother Ṣubḥ-i Azal and formed a new group within the Bābī movement, declaring himself to be God’s final prophet. In a garden in Baghdad, he introduced himself to his followers as Bahāʾu’llāh, meaning “the Glory of God.” From that point onward, he became known as Bahāʾu’llāh, and his followers came to be called Bahāʾīs.

Thus, a movement that had begun with the search for the Hidden Twelfth Imam ultimately emerged before the world in new, separate, and distinct religious forms.

In this way, Bahāʾu’llāh separated from his brother Ṣubḥ-i Azal’s Bābī group and formed his own independent branch, known as the Bahāʾī Faith. This deeply angered his brother Ṣubḥ-i Azal, and both brothers began actively promoting their own groups. At this stage, a large number of people from the Bābī community, which had earlier followed Ṣubḥ-i Azal, accepted the ideas of Bahāʾu’llāh and became Bahāʾīs. As a result, a serious conflict began between the two brothers over leadership and succession within the Bābī movement.

According to Bahāʾī sources, Ṣubḥ-i Azal even tried to poison his brother Bahāʾu’llāh. Although Bahāʾu’llāh survived, the effects of the poison reportedly caused his hand to tremble for the rest of his life. During their stay in Baghdad, the number of Bahāʾu’llāh’s followers continued to grow.

Expulsion from Iran and Journey to Istanbul and Edirne

After Bahāʾu’llāh announced his new religious claims and prophethood, the Qajar government of Iran approached the ruling power of Baghdad at the time, the Ottoman Caliphate, arguing that the ideas of Bahāʾu’llāh and his brother Ṣubḥ-i Azal were dangerous for Iranian society. For this reason, Iran demanded that they be expelled from Iraq, a neighboring country. As a result, the Ottoman authorities ordered both brothers to leave Baghdad and move far away from the Iranian border, to Istanbul, Turkey.

Bahāʾu’llāh also went to Istanbul, but after staying there for three months, he was sent away from Istanbul to Edirne, a region in European Turkey. In Edirne, Bahāʾu’llāh had greater freedom to spread his ideas. There, he openly declared that he had brought a new religion and invited people to join this new faith.

He addressed both Muslims and Christians, claiming that he was the promised Messiah whose coming had been foretold in their religions, and therefore they should accept his religion. Bahāʾu’llāh also sent many missionaries to his homeland, Iran, where a large number of followers of the Bāb were living. These missionaries told the Bābīs that the figure whose coming the Bāb had promised was in fact Bahāʾu’llāh, and that all Bābīs should follow him and become Bahāʾīs. As a result, almost all Bābī followers accepted Bahāʾu’llāh and joined the Bahāʾī Faith.

Spreading the Bahāʾī Faith

Bahāʾu’llāh also wrote letters to major rulers of his time, including Napoleon III of France, Queen Victoria of Britain, Tsar Alexander of Russia, and the Pope of the Christian world. In these letters, he claimed to be a prophet and advised them to abandon war and conflict and to live in peace and harmony.

Because of internal conflicts and the spread of their new religious movements, the Ottoman Empire expelled both brothers from Turkey in 1868 and sent them to imprisonment in different regions. Ṣubḥ-i-Azal was sent from Turkey to Cyprus (then under Ottoman rule, near Greece), where he spent the rest of his life. Over time, the number of his followers became very small.

Exile to Palestine: Life and Work in Acre (ʿAkkā)

On the other hand, Bahāʾu’llāh, along with his companions, was sent from Turkey to the Palestinian city of Acre (ʿAkkā), where he was imprisoned. During his imprisonment in Acre, Bahāʾu’llāh wrote his most important book, the Kitāb-i-Aqdas, which is considered the holiest book of the Bahāʾī Faith. In this book, he outlined the main laws and principles of his religion.

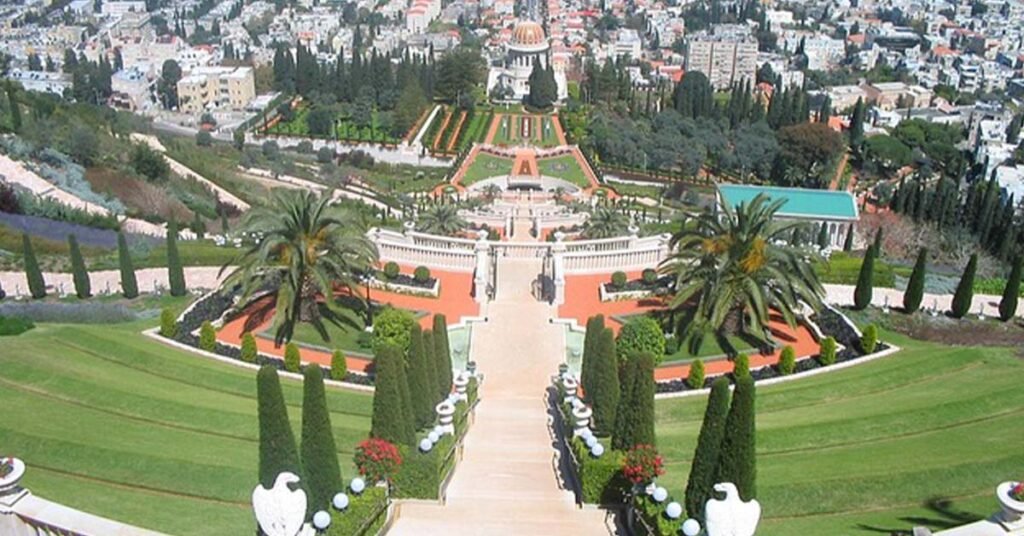

In 1877, Bahāʾu’llāh was released from prison and continued his religious activities in Acre. He expanded his preaching, and as a result, the Bahāʾī Faith spread to Egypt, Anatolia, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and India. In 1879, Bahāʾu’llāh and his followers rented a large mansion in Acre, from where he continued his mission for the next thirteen years. On 29 May 1892, Bahāʾu’llāh passed away in this mansion at the age of 74. He was buried there, and today the same building serves as his shrine.

After Bahāʾu’llāh’s death, the issue of succession arose once again. One of his sons, ʿAbdu’l-Bahā, claimed that he was the new leader of the Bahāʾī community, while his half-brother, Mirza Muhammad Ali, also claimed leadership and accused ʿAbdu’l-Bahā of violating the principles of the Bahāʾī Faith.

Succession of ʿAbdu’l-Bahā and Global Spread

However, ʿAbdu’l-Bahā claimed that before his death, his father Bahāʾu’llāh had appointed him as the head of the Bahāʾī community. Bahāʾu’llāh had also declared that only ʿAbdu’l-Bahā had the authority to interpret his teachings and laws. Because of this, the vast majority of the Bahāʾī community accepted ʿAbdu’l-Bahā as their new leader.

ʿAbdu’l-Bahā shifted the center of Bahāʾī missionary activity to North America, which gradually led to thousands of people joining the Bahāʾī community in the United States. At the same time, he traveled to many countries, spreading the Bahāʾī message at a global level. ʿAbdu’l-Bahā passed away on 28 November 1921 and was buried in the same complex where his father’s shrine is located.

Before his death, ʿAbdu’l-Bahā appointed his grandson, Shoghi Effendi, as his successor and Guardian of the Bahāʾī Faith. Shoghi Effendi instructed the American Bahāʾīs to spread the Bahāʾī message throughout the world. However, during this same period, Bahāʾīs in Iran, the Caucasus, and Central Asia faced severe persecution, violence, and religious oppression.

In 1957, Shoghi Effendi passed away in London and was buried there. After his death, an institution called the Universal House of Justice was established to guide and administer the Bahāʾī Faith. This institution continues to oversee Bahāʾī affairs today.

Moreover, after the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979, strict measures were taken at the state level against followers of the Bahāʾī Faith. These measures included arrests, imprisonment, and strong social pressure. In some cases, reports also emerged of the desecration and destruction of Bahāʾī cemeteries.

Core Beliefs of the Bahāʾī Faith

Since the founders of the Bahāʾī Faith came from Shia Islam and the wider Abrahamic religious tradition, the Bahāʾī religion also believes in the oneness of God and does not accept any partner with Him. However, in Bahāʾī teachings, God is remembered by different names, such as Allah, Yahweh, Brahman, and others.

The Bahāʾī Faith recognizes Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon them), as well as Krishna of Hinduism, Zoroaster of Zoroastrianism, Buddha of Buddhism, the Báb of Bábism, and Bahāʾuʾllāh, as divine messengers or Manifestations of God who brought God’s message to humanity.

The Bahāʾī Faith also places strong emphasis on science. According to Bahāʾuʾllāh:

“Religion without science leads to superstition, and science without religion becomes materialism.”

Laws, Practices, and Community Life

According to Moojan Momen, Bahāʾu’llāh explicitly abolished many beliefs and practices that had become common in other religions. These include the priesthood system, declaration and enforcement of holy wars (jihad), asceticism and renunciation of the world, confession of sins, burning of books, use of pulpits, and declaring certain people or objects as impure.

Bahāʾu’llāh also prohibited his followers from engaging in certain actions, such as slavery, begging, kissing hands, using intoxicants and alcohol, gambling, carrying weapons unnecessarily, and homosexuality.

In the Bahāʾī Faith, every adult is required to pray three times a day, called Salāt. Ablution (wudū) is performed before prayer, and during prayer, followers prostrate before God, facing the shrine of Bahāʾu’llāh.

The Bahāʾī calendar consists of nineteen months, each with nineteen days. During the last month, called ‘ʿAlā’, Bahāʾīs observe a nineteen-day fast.

Followers also contribute a portion of their income as a donation to the Bahāʾī administration, known as Huquq-u’llāh.

Bahāʾīs estimate their global population at over seven million, though independent verification is difficult. The faith is often considered the ninth-largest and fastest-growing religion in the world, with significant communities in Iran, India, and various countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

References

1. Momen, Moojan. The Baha’i faith: a short introduction. Oneworld Publications, 1999.

2. Smith, Peter. An introduction to the Baha’i faith. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Who Was the Bāb? Origins of Bābism and the Bahāʾī Faith in 19th Century Iran

History of the Ahmadiyya Qadiani Movement: From Declaring Others Non-Muslim to Facing Exclusion

1 thought on “Who Are the Bahāʾīs? From Shia Imam Mahdi to the Bāb and Bahāʾu’llāh – The Rise of the Bahāʾī Faith (Part-Two)”